Travel to a Hidden Coffee Farm: A Remote Colombian Adventure

A hidden gem in the countryside of Colombia

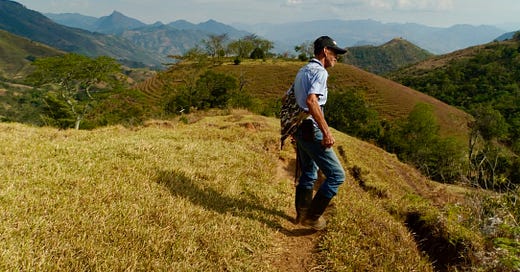

A blazing sun shone on our backs as we climbed up a steep mountainside. It was only 7:30AM and the heat of the day was already sending sweat trickling down on our necks. Around us was nothing but vastness. Surrounded by massive mountains, normally bright green but this time of year we found them dry and browning. Our local contact, Hector, easily 50 years older than me, hiked up ahead of us with ease while I struggled to keep up. We were an hour hike away from the coffee farm which was unreachable by car. Yes, there are still remote places in the world unreachable by automobiles. The farm family lives 3 hours away by foot on a single track steep path from the closest town. The coffee they pick by hand is brought to town by mule. Have you ever wondered if maybe your morning cup of coffee came from somewhere like this?

Journey to the Coffee Farm

My dad, uncle, and I had driven from Medellin at the crack of dawn that morning to the tiny town of Titiribi where my dad spent his summers growing up. A taxi driver had told my uncle about his relative’s coffee farm near Titiribi and the three of us jumped at the chance to go shoot a mini film about the remote coffee farm.

After a few hours on backroads and breakfast of arepas off the side of the road, we reached a gravel road per Hector’s directions. He said he’d meet us under a small “tienda” with a metal tin roof. We found the tienda which was a sheet of metal held up by a couple wood beams. He greeted us like old friends and told us to leave the car there in the middle of the road. No other cars would be passing by. We’d continue the rest of the way by foot.

My lungs huffed and puffed from the lack of oxygen as we climbed. The three of us were not accustomed to this elevation and heat. Meanwhile Hector scrambled along ahead of us. There were no sounds other than the wind and chirping birds. The air was hot but clean and fresh. The landscape reminded me a bit of West Texas with low shrubs, yellowing grass, and hills. But slowly it changed into a little bit of a jungle. Suddenly surrounding us were green coffee plants. Some small as a little dog and some twice my size. The coffee cherries varied from green to bright red. Then we hiked past a grove of cacao trees. Big cacao pods hung from the trees. Some ripe yellow and others burnt brown.

I reflected at how often we don’t even know where our food comes from or what it looks like in it’s original form. Despite being a huge chocolate lover, I had never seen a cacao plant out in the wild before. I reached out and touched a cacao fruit. It’s thick husk protecting the goodness inside.

Hector stopped ahead and pointed a little red house in the distance. The first creatures greeting us upon reaching the farm were three huge mama pigs and about 15 of the cutest piglets. Then came the rest of the family, another man also named Hector (his brother-in-law), his wife, and her mother.

They explained to us that they’d lived on this land all their life. Almost 70 years, and they’d live here until their last days. They hardly ever leave their farm because of the long journey to town. Sometimes Hector takes a mule (which still takes a few hours), but his wife, Flor and her mother hardly ever leave. Flor’s elderly mother has to go to town for doctor’s appointments on occasion and three men have to carry her on a sheet turned into a make-shift stretcher through the mountain trail for 3+ hours.

Intertwined with the Land

The house is humble and small. A couple of walls, an open air kitchen, a bedroom, and a wonderful little porch overlooking the mountains and flowers. They have a solar panel providing light, cold water from a well, and a little bit of cell service.

“We might not have a lot of luxury, but we have peace,” said Flor. She said nothing compares to the simplicity of life they lead there. They take care of the land, the land takes care of them, and they take care of each other.

But living in “el campo” or the countryside isn’t easy. Years of hard physical labor working in the field, working on the house, growing food to sell and to live. There is no access to grocery stores, doctors, transportation, or consumer goods nearby. For people who live in rural areas they have to do everything themselves— build and maintain their homes, work the land, from dawn till dusk.

When we arrived, they ushered us under the shade of the porch and Flor brought out cold glasses of fresh mango juice straight from their trees. Hector shared how in a few generations this type of family farm will disappear. They are perhaps the last generation, because the younger people aren’t interested in tending to the land. He said their kids grew up and moved to the city. How multinational companies are coming in and purchasing hundreds of acres of land and bringing in employees to farm it. The magic and passion for tending to the land from generation to generation is getting lost.

But he said they feel lucky to live the way they do. They don’t go to grocery stores, they grow the food they eat every day— potatoes, plantains, fruits and vegetables. They have pigs and chickens. They barter with the neighbors for rice or other provisions. They make the traditional Colombian cacao drink with cacao from their own trees. The coffee they drink, however, is the leftover “not-so-good” beans because they sell the good ones.

In the afternoon, they took us on a hike even farther up the mountain to see the coffee trees. By this time it was 106ºF (about 42ºC) and Hector said this was the hottest year they’ve ever experienced in close to 70 years. Due to Colombia’s geographic position close to the equator, there are no seasons (summer, winter, spring, fall) and usually the only fluctuations are rainfall. They told us it hadn’t rained in months and the coffee plants and other vegetations were severely impacted. Soil was completely dry and loose, banana trees were falling from lack of water, and cacao was not producing well. Climate change and an El Niño year are severely impacting their livelihoods. Not only are they struggling to produce enough to sell, but they are scarcely producing enough to eat themselves.

When we returned to the house, Flor had whipped up lunch for us— another example of just how hospitable and generous these “campesino” or countryside families can be. We hadn’t expected to have lunch there yet they insisted. So we all sat on the porch and shared a meal straight from their land. Plantains had never tasted so good.

Folklore

Over lunch, Hector shared tales of the original indigenous people who inhabited this land. He said he’s found “Guacas” while working on the farm, which are ancient burial sites where he found human skulls and bones inside pot-looking ceramic artifacts. He said that usually every year on Easter Sunday at night, strange lights glow around these burial sites. He also said a few years ago he discovered a hidden tunnel carved through the mountainside. He believes it was built by indigenous people as a shortcut to the town. But that it creeped him out so much that he it boarded it up.

It’s hard to describe the peacefulness you can feel from up their on their farm tucked between the coffee trees and under the shade of the banana trees. Not a car can be seen or heard, no street lights, no sirens, no other people, no humming of electronics. But you can hear the pigs squeal, bees buzz, Flor washing clothes by hand, and both Hectors tending to the land.

Once the sun sank a bit, we dunked our heads in the cold well water and began the trek back to the car. We stopped a few times to sit and enjoy the silence.

When we reached the tin roof tienda, we sat on tree stump chairs and an older lady greeted us. We ordered some cold beers and coca-cola followed by tinto (black coffee) to recharge. She walked into her little house and brought us out our drinks. I took a nap on a tree log and felt the wind in my face.

We walked to our car and said goodbye to Hector. He was off to forage a herb in the mountains for healing arthritic pain, and we hopped in the car on the way back to civilization.

Ten minutes after we got in the car, the sky turned grey and thunder clapped. A huge thunderstorm rolled through. Rain. It poured heavily for hours. Hector texted us saying we had brought them rain.

Nature’s Goodbye

Our day spent at a remote coffee farm nestled in the Antioquia region of Colombia was a profound journey into a world of simplicity and connection with the land. We felt a wave of gratitude as we shook hands with Hector and his family who were so generous with us. I loved knowing that such places still exist where people and nature live so intertwined. It’s a reminder of the fragile balance between tradition and modernity, and the challenges posted by climate on on these remote communities.

As we drove back to the city, the unexpected rain that followed felt like a sign of nature's response to our shared experience, a brief moment of interconnectedness. (PS: check out the photo gallery below and stay tuned for our short film coming out in a few months).

It's Your World 🌎 is a reader-supported publication. To support and receive new posts, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Wow! How wonderful you were able to visit and learn and witness. It makes me sad that countries like the US are destroying the earth’s climate balance, which will mean great hardship for families like this, and this simple, beautiful way of life where connection with the land is part of every day, every moment. Thank you for writing and sharing this!

A beautifully expressed experience. 🙏