This is part 2 of the the Japan ikigai story. If you missed part 1, you can read it here first.

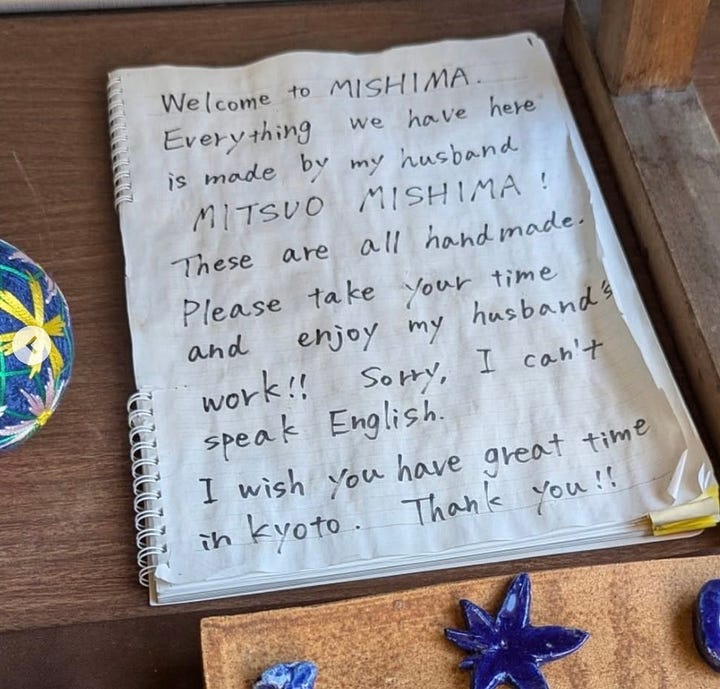

If we pay attention, omens often flag our path. The first was the friendly elderly woman who greeted me at the door. Then, whenI walked in, I saw this sign:

“Welcome to Mishima. Everything we have here is made by my husband Mitsuo Mishima! These are all handmade. Please take your time and enjoy my husband’s work!! Sorry, I can’t speak English. I wish you have a great time in Kyoto. Thank you!!

Inside the walls were lined with beautiful pottery. Waves of blue and yellow cups, plates, and tea sets filled the space. As I scanned the room in awe, a younger woman welcomed me and spoke a little English. Despite the language barrier, we began conversing with the help of Google Translate, and I learned her name was Rie.

Before I knew it, the older woman disappeared behind a curtain, then returned with a bright red iced tea. She signaled for me to sit next to her on the bench while she poured tea into little glasses for herself, Rie, and me. We sat there, smiling at each other, and I started asking questions about the pottery

A beautiful blue tea set caught my attention—delicate, elegant, yet not industrial. The teapot handle looked like braided wooden branches. Rie told me it was the last of its kind that Mitsuo had made. As he aged, crafting such intricate pieces became more difficult. This was the last intricate teapot he ever made.

We all experience those internal dilemmas when we deeply want something but hesitate because of the price. The teapot and two cups cost over $250, and I was on a traveler’s budget. But I thought about their kindness and the stories they shared about Mitsuo crafting these pieces by hand. I felt a special energy radiating from them, so I decided to buy the set.

Another problem arose: the pottery was too fragile to carry in my backpack without breaking. Then I remembered Steve Jobs’s story about buying a tea set and having it shipped home. I suggested this to Rie. She said they had never mailed pottery before but was willing to try.

Before I left, Rie asked if I could return in an hour. Mitsuo would be back, and she thought he would enjoy meeting me. I stepped out and decided to check out the famous temple in the meantime. It swarmed with tourists, selfie sticks, GoPros, and influencers. Quickly overwhelmed, I found an exit and returned to the safe haven of the ceramic shop with my new friends.

Mitsuo greeted me with a gentle bow and a smile. He didn’t speak English, but with Rie and Google Translate, I learned he had been making ceramics since childhood. At 80, he was still dedicated to his craft. Suddenly, he looked me in the eyes and repeated a phrase. It took a second, but I thought I recognized the words. “Ikigai, ikigai,” he repeated with a twinkle in his eyes.

The Ikigai book doesn’t mention it, but I know Steve Jobs’s words by heart: “Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do. If you haven't found it yet, keep looking. Don’t settle. As with all matters of the heart, you’ll know when you find it.”

I learned that quote when I was 15, and since that day, I committed to pursuing work that makes my heart happy, that I’m good at, and that is of positive impact to other people. But I hadn’t connected it to ikigai until now. It’s easy to see a figure like him and assume it’s easy for him to say it. But my experience in Mitsuo’s ceramic shop changed that.

Sometimes the line between life and work gets blurred in a negative way, but I think there are ways it can blur and become positive— just like for Mitsuo who finds pure joy in his lifetime craft.

Mitsuo discovered his passion for art at a young age (what you love). He became a skilled craftsman through time and dedication (what you are good at). He discovered that functionality, attention to detail, and beauty in imperfection are things humans care about (what the world needs). Plus, he realized people could make use of his craft— as a tea set, a mug, a plate (what you can be paid for). At the intersection of these four elements, magic happens. It’s just called different things by different people.

Learn by Doing

A tea set is just a tea set. But objects carry emotional connections and energy. That’s why something feels more special when it has a story. As if to demonstrate this firsthand, Mitsuo and Rie led me behind the curtain to his pottery studio.

We all took off our shoes and entered. It was humble, dimly lit, and tiny. A hole in the ground held the potter’s wheel, with a lump of clay resting on top. Dried clay and paint speckled the windows and floors. A small red cushion sat next to the wheel. Mitsuo crouched down with remarkable agility and started spinning clay.

He has done this for 70 years. His hands must be strong yet gentle, precise yet flexible. He moves effortlessly from standing to sitting for hours. When he saw me filming, he motioned for me to put down the camera and sit on the floor pillow.

I had never spun clay before and struggled to shape it. With patience, Mitsuo sat beside me, guiding the way. His wife and Rie watched as he showed me how to make a bowl. He kept talking, explaining, though I understood nothing. Still, in the end, I shaped a bowl, and he smiled proudly. Moments like these remind us that language isn’t always a barrier—we connect meaningfully through gestures, presence, and shared experience.

Before I left, Mitsuo made sure all took a selfie, capturing the moment forever. A few days later, Rie emailed me, expressing gratitude for my visit and our connection. We had spent wonderful time together, communicating in the language without words. She said Mitsuo loves showing his customers the video of me spinning the clay.

Hidden Lessons in a Tea Pot

A few weeks later, the tea set arrived intact in Texas. Its braided wooden handle and blue paint, with small imperfections, carried the essence of its maker and the heart of his shop— his wife and Rie too. I hope we all find our ikigai, just as Mitsuo has.

Let’s not forget Mitsuo’s wife and Rie embody the omotenashi spirit of wholehearted hospitality. For after all, it was their energy that drew me into their shop. Just as Mitsuo shaped the clay, they shaped my experience as a guest not only in their shop, but in their country. It’s these fleeting yet meaningful connections that prove that fulfillment often lies in small intentional acts of kindness.

In Japan, people understand that life is fleeting—things, people, and experiences exist only for a moment. They have a phrase for this: Ichigo Ichie. Each encounter, whether with friends, family, or strangers, is unique and will never be repeated. This story of Mitsuo’s ceramic shop is one of those moments. No matter how hard we try, I will never be replicated.

While this perspective carries some melancholy, it also holds beauty. The Japanese recognize that the fleeting, the changing, and the imperfect have their own kind of perfection. Ikigai, too, is imperfect. There is no perfect balance between work, family, and duty. But there is beauty in the journey of striving closer to our own ikigai, whatever it is for each of us.

Part 1 is below:

A Souvenir that Actually Matters (Part 1 of 2)

With a swiftness of a much younger person, the 80-year old Japanese man sat cross-legged on a thin red floor cushion in a dimly lit, closet-sized back room. His name was Mitsuo Mishima. In his little pottery studio behind his ceramic shop in Kyoto, he taught me about